No Slam Dunks · Invest in the Magnificent Seven? · It May Be Time for Active Management

Portfolio Advice, Talking Points, and Useful Resources

- There are no slam dunks in investing. The only certainty is uncertainty.

- The Magnificent Seven has been magnificent. Don’t expect that to continue forever.

- Active management will shine again. When it does, some of its historical disadvantages will have lessened.

No Slam Dunks

There are no slam dunks in the markets, at least in terms of economic calls. Remember last year’s sure-fire call of an economic recession? What about the near-certain aggressive interest rate cutting the Federal Reserve was supposed to do this year?

When it comes to investing, the only certainty is uncertainty. To prepare, investors need to consider what is probable in the markets, but also consider what is possible.

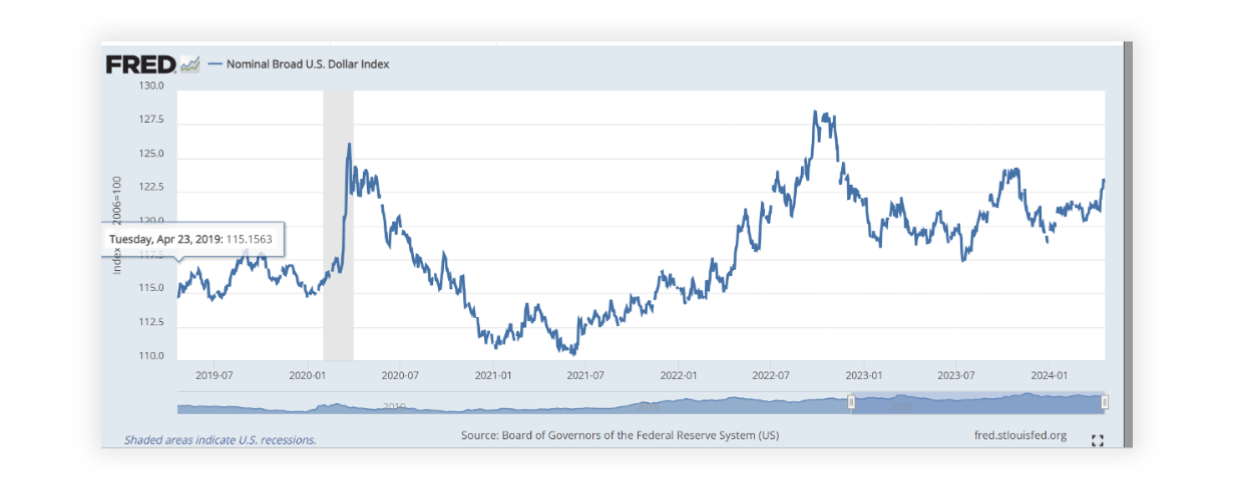

What might be considered some slam dunk views in the market now? One is that the U.S. dollar will continue to get stronger relative to international currencies, and in turn U.S. markets will outperform on the back of this currency strength. This expectation is built on the changing view that the Federal Reserve will not cut rates as aggressively as many had expected, partly because economic growth has been stronger than expected and partly because inflation hasn’t been vanquished. Primarily because of this changing expectation, the dollar has indeed strengthened in recent months. It regained its losses over the last year and is now marginally higher year-over-year.

All else being equal, dollar strength suggests U.S. stock market outperformance. However, other factors should be considered. For instance, the U.S. market has much heavier exposure to growth/tech stocks than other non-U.S. stock markets. If growth/tech starts to underperform, and arguably that has been the case since early March, the U.S. stock market may begin to lag. As of this writing, since early March the dollar is up smartly, but the overall U.S. stock market has not outperformed.

Is it even a slam dunk that the dollar will strengthen in the years ahead? The dollar is considered expensive, but perhaps more importantly, it has had lower price highs over the last five years despite U.S. economic dominance. Could other factors, such as the U.S.’s massive debt and its aggressive war-and-depression-like deficit spending be factored in by the markets? The U.S. has had superior relative economic growth of late, and many investors expect that to continue. But without that extraordinary fiscal spending, is the growth still superior? As Strategas’s chief economist, Don Rissmiller, has pointed out, U.S. growth has been impressive in recent years, partly due to massive fiscal spending and partly due to immigration. Regarding the latter, immigration has helped provide a necessary supply of labor (particularly as U.S. manufacturing has brought factories and jobs back onshore) and in turn increased economic demand.

Currently, U.S. growth expectations are quite elevated. Double-digit earnings growth is expected for the next three years. Note however that only twice since the 1980s have U.S. companies managed three consecutive years of earnings growth. It happened in the mid-1990s and in the mid-2000s. Since 2008, actual earnings have come in below beginning of the year expectations every year, except for 2018.

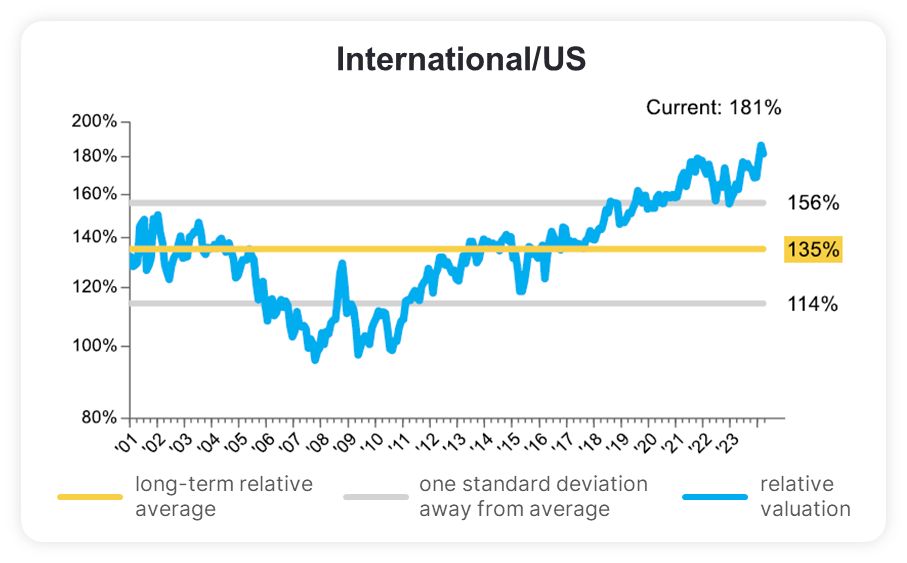

The recent run of short-term, non-U.S. returns being competitive against U.S. returns could signal a long-awaited turn in relative performance. Even if it does not, the turn will eventually happen, and it could last for years. For example, 15 years ago, non-U.S. markets traded at par with the U.S. market in terms of valuations. Now, the U.S. trades at an 81% premium.

Source: Factset

The chart above illustrates an equal weighting of four valuations: price/earnings, price/sales, price/cash flow and price/book ratios since the beginning of the century. Another way to look at valuations is through CAPE ratios and other cyclically adjusted valuation measures, which show average earnings over the last 10 years. No surprise here, but the U.S. is indeed expensive.

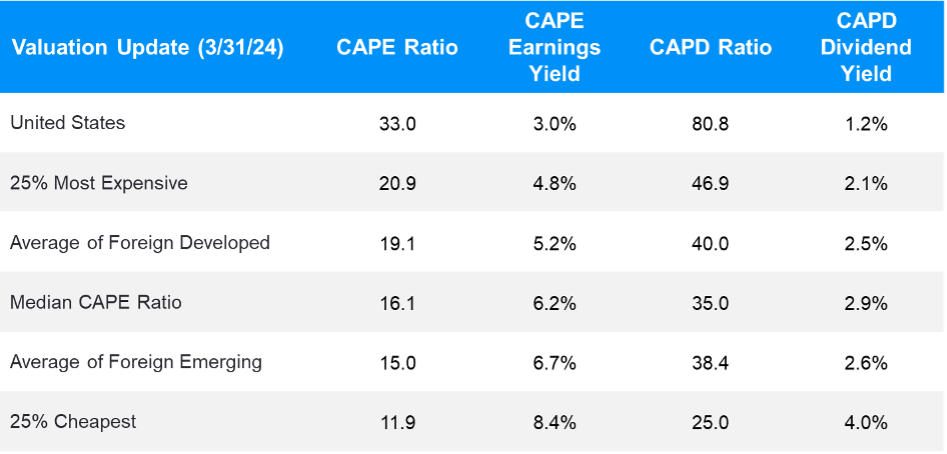

The table below shows CAPE ratios from around the world as of March 31. These numbers can be assessed by formulating a crude expected return calculated via earnings yields (the inverse of the CAPE ratio). In this case, the U.S. has a 3% earnings yield when the median CAPE ratio of stock markets around the world is 6.2%. That suggests the U.S. could underperform by more than 3% per year in the next decade. Some analysts fortify that expected return by reviewing dividend yields. Using the cyclically adjusted dividend yield (CAPD), the U.S. market appears expensive again, with a yield of 1.2% instead of 2.9%. That’s another ~2% of expected underperformance.

Source: Idea Farm

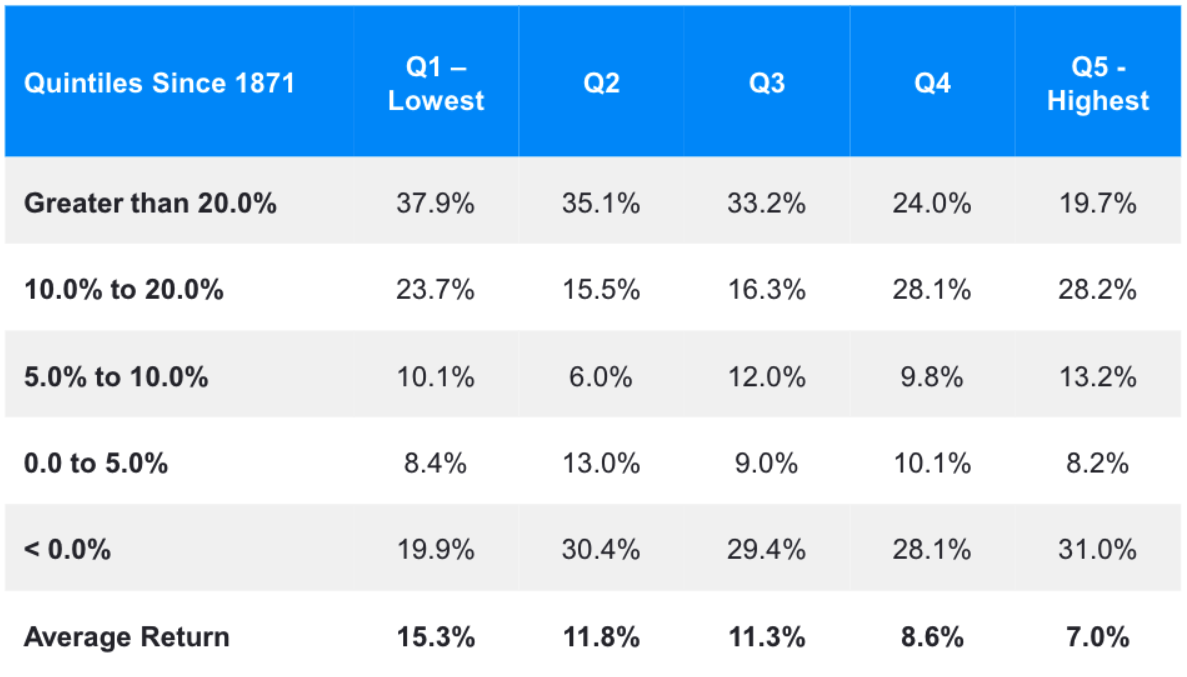

Given that high valuation stocks have outperformed recently, at least in the U.S., it’s popular to say that valuations don’t work in the one-year time frame or that valuation measures simply may not work anymore. The first point isn’t true historically. The table below breaks down valuations into quintiles. The highest quintile, the most expensive stocks, have returned 6.9% per year on average. The lower the valuation, however, moving right to left from high to low, the higher the average return over the following 12 months. The first quintile of the lowest valuations has more than twice the return of the most expensive stocks.

U.S. Market Historical Return Probabilities

Equity Market by Valuation Quintile – P/E

This table uses historical returns since 1871 to show the probabilities of the forward twelve-month return (left column) of the stock market at different valuation levels using P/E Ratios (Q1 being time periods with the lowest P/E; Q5 being periods with the highest). A common misconception is that high market valuations result in negative forward returns. Although Q5 is on average the period of lowest forward returns, it still averages a nominal return of 7.0% with an overall 69.3% probability of positive return.

Source: Stock market data is from Yale Professor of Economics Robert Shiller.

Numbers range 1871 – 3/31/2024. The sum of the figures may be lesser or greater than 100% due to rounding. As of 3/31/2024. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Individual client accounts may vary. 1 Year Forward returns matched with valuation quintiles determined by P/E. Breakpoints of 367.

Q1: P/E is less than 10.85; Q2: 10.85-13.59; Q3: 13.59-16.32; Q4: 16.32-19.08. Q5: 19.08+.

Another potential slam dunk view, which most investors now expect, is strong economic growth. However, with commodity prices, notably gas prices, sharply higher and higher interest rates, is it a slam dunk? We will have a final-term president next year. How will that impact the positive economic tailwinds of fiscal spending and strong immigration?

Another popular view is that short-term rates are more likely to fall than rise, and mortgage rates will fall with them. When it comes to short-term rates, investors should consider what they’re rooting for. For mortgage rates to fall, an increase in short-term rates is more likely to help. Higher rates typically help reduce inflation. The Fed directly controls only the short end of the yield curve, i.e., the shortest maturities. The market controls the longer end (longer maturities). If the market believes inflation is not under control, but the Fed cuts short-term rates, longer-term rates may rise even further. That surely won’t help mortgage rates.

There is one slam dunk that remains: diversification. There is a reason it’s considered the only free lunch in investing (though it doesn’t mitigate risk entirely). While it doesn’t necessarily prevent losses during periods of extreme market stress, diversification does with mathematical certitude help reduce overall portfolio volatility.