What and Who Creates the Behavior Gap? · Why Should Investors Care About Value Investing? · How Should Younger Investors Use Expected Returns?

Portfolio Advice, Talking Points, and Useful Resources

- The behavior gap — the difference between an investment's returns and the returns investors actually achieve — has multiple causes, and it’s not entirely the individual investor’s fault.

- What is value investing, and why should investors care? We outline three key takeaways for investors to consider when building diversified portfolios.

- How should investors — especially younger ones — think about capital market assumptions, also known as "expected returns"?

As we approach the final month of the year, investors are reflecting on several key considerations. First, how should they evaluate their portfolios’ performance this year, and what adjustments should they consider for the year ahead? In this month’s report, we explore three topics that may help guide these assessments. Ultimately, our advice remains consistent: Long-term investors are best served by staying invested, diversified, and disciplined. We hope you find this analysis valuable. If you have any feedback or questions about the material, we encourage you to reach out.

What and Who Creates the Behavior Gap?

By Rusty Vanneman, CFA, CMT, BFA, Chief Investment Strategist

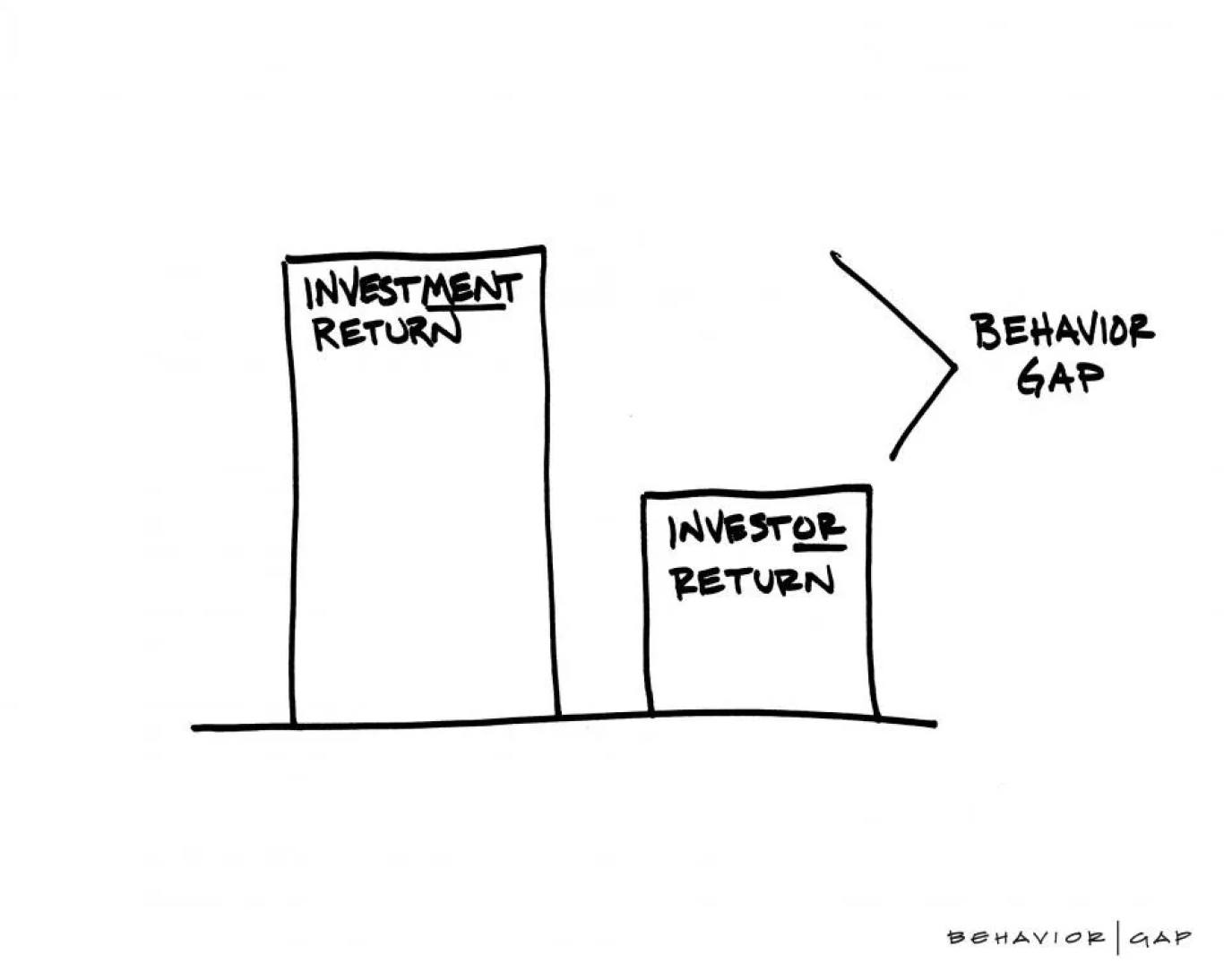

For years, we’ve highlighted one of the most critical issues in investing — arguably the top issue — the behavior gap.

Source: Carl Richards, OPS Quarterly Reference Guide.

The behavior gap reflects the difference between an investment’s return and the return investors actually experience in that same investment. The disparity is often due to timing — specifically when an investor decides to dive into or pull out of the market based on emotion rather than sound financial planning or economic rationale. This behavior frequently runs counter to an investor’s financial plan. At Orion, we are passionate about addressing this challenge. Whether it’s through insights from our chief behavioral officer, Dr. Daniel Crosby, and his team at Orion Behavioral Finance, or via thought leadership from our investment strategy team, we dedicate ourselves to closing the gap.

What drives suboptimal returns? Often, it’s performance chasing — buying after prices have surged or selling after they’ve dropped. It’s a cycle we’ve all seen play out; yet, it remains one of the most difficult traps to avoid. Numerous studies, listed in our OPS Quarterly Reference Guide, including findings from the Vanguard Advisor’s Alpha study, show that financial advisors deliver value far beyond their fees. Arguably, their greatest contribution is their ability to keep investors balanced, diversified, and aligned with their financial plans.

Why does performance chasing hurt investors? It’s a complex issue, particularly when juxtaposed with the familiar disclaimer, “past performance is not indicative of future results.” To delve deeper, let’s borrow some wisdom from John Rekenthaler’s swan song article, "Do Historical Stock Market Returns Matter?" Rekenthaler, who is retiring soon, has long been a thoughtful voice in our industry, and his final piece provides timeless insights.

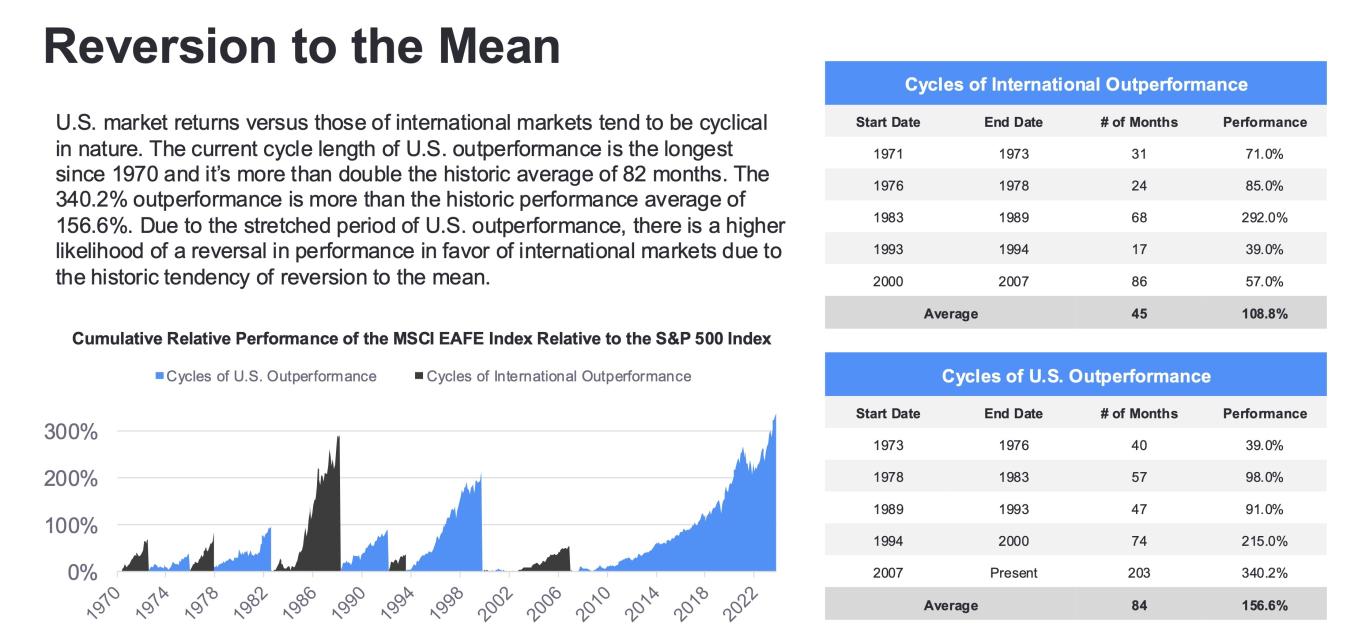

- Losers often become winners, especially when considering longer-term performance. Nobel laureate Richard Thaler and co-author Werner De Bondt, in their seminal paper “Does the Stock Market Overreact?” demonstrated that stock portfolios that underperformed over the previous 36 months tended to outperform moving forward, while past winners lagged. Their research aligns with the legendary value investing principles of Ben Graham: Cheap, unpopular stocks often deliver future outperformance.

- Winners can keep winning, especially in the short term. Narasimhan Jegadeesh and Sheridan Titman’s paper, “Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency,” presented a different view. Over shorter periods (three to 12 months), past winners continued to outperform, and past losers underperformed. In essence, the nature of historical returns depends on the timeframe being analyzed.

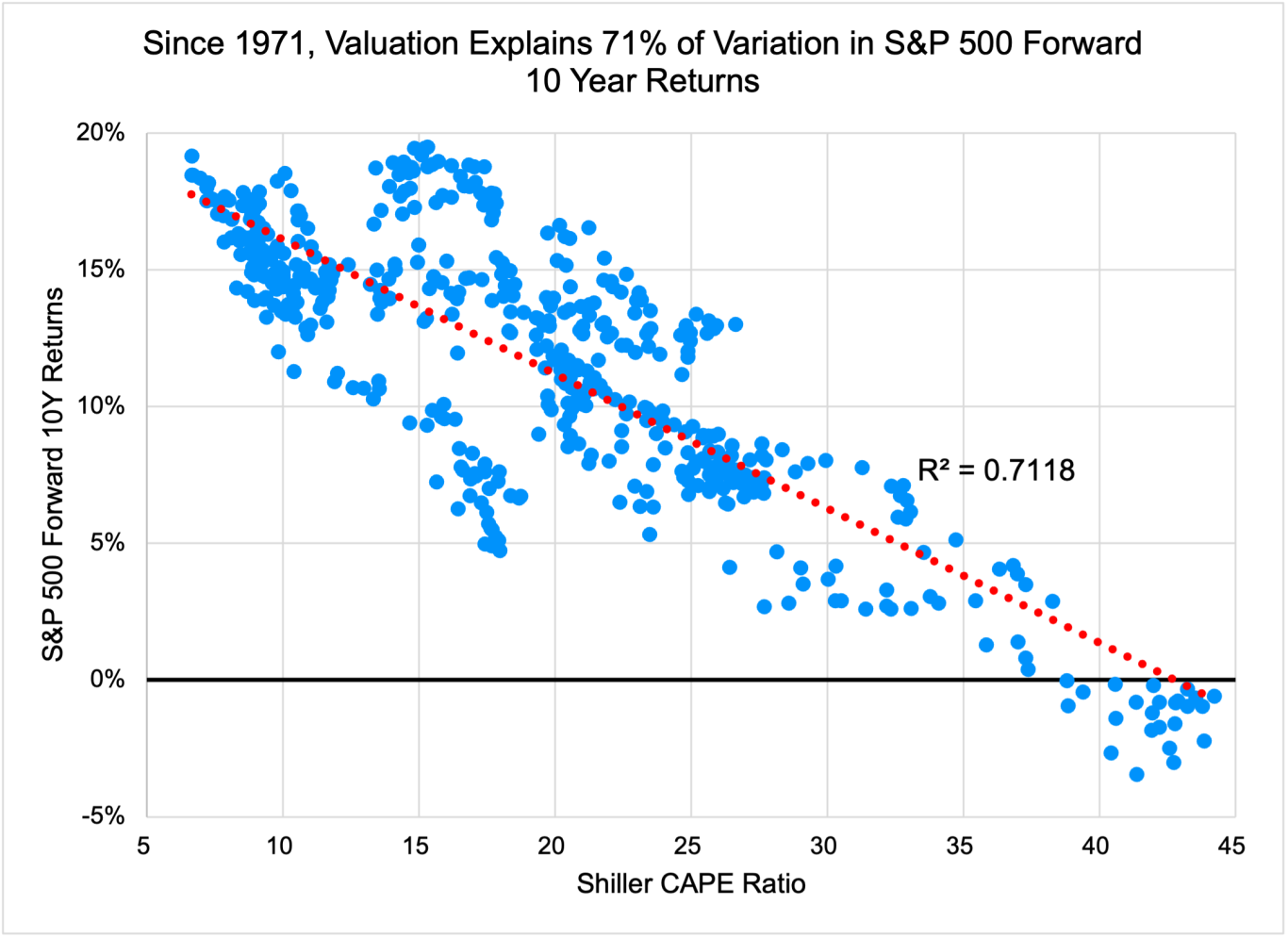

What does this mean for investors? Here’s the takeaway: Longer-term investors should heed the historical pattern that what outperformed in recent years is likely to underperform in the years ahead. While there’s always a chance that recent winners continue to win, the odds are not in their favor. Think of it like a football team that’s a two-touchdown underdog. They could win, but the probabilities are stacked against them.

For those drawn to short-term trends, it’s best to leave momentum and relative-strength strategies to experienced professionals. These approaches demand rigorous analysis, discipline, and emotional resilience. In other words, it’s a full-time job and best left to those trained and incentivized to manage it with precision.

One last consideration — while individual investors often bear the blame for performance chasing, two other factors deserve scrutiny:

- The use of illustrative portfolios. Many professionals use three-year performance numbers as a key input when evaluating investments or managers. In my experience, the three-year number is probably the most singularly used input in assessing investment management performance and deciding to buy or sell managers. While it’s a good data point to understand behavior and relative risk, this practice often perpetuates underperformance in returns moving forward, as the studies above show.

- Many professional money managers deserve some of the blame. Even professional money managers aren’t immune to performance-chasing behavior. As John Maynard Keynes famously said, “It is better to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.” Many managers, faced with mortgage and tuition payments, stick with the herd to preserve their paychecks, even when the data suggests otherwise.

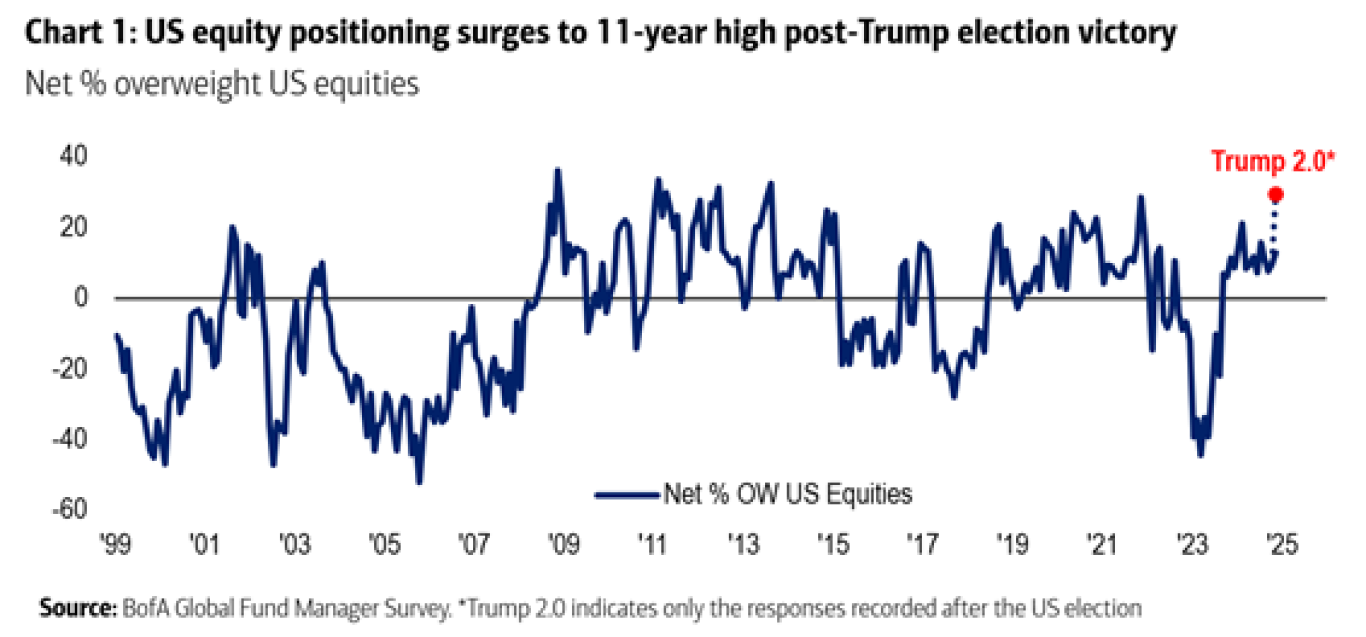

Right now, portfolio managers are the most overweight U.S. equities we’ve seen in more than a decade. This comes after years of outperformance and in one of the most overvalued U.S. markets in history — conditions that historically suggest below-average returns ahead.

Source: BofA Global Fund Manager Survey. *Trump 2.0 indicates only the responses recorded after the US election.

Bottom line: Closing the behavior gap requires discipline. Whether an investor is investing for themselves or on behalf of others, success hinges on staying true to a financial plan and investment mandate. The road isn’t always easy, but with a steady hand and a long-term perspective, it’s a journey worth taking.